What an extraordinary example to choose: it means precisely the

opposite of what Cowan says! The whole point about this famous biblical passage

is that the lack of a name for David’s love made it difficult to speak about

it. It manifestly does not demonstrate a ‘simple’, ‘comfortable’

acceptance of something common – on the contrary, it vividly illustrates the

struggle to describe something ‘wonderful’ and very special and beyond the

common conceptions available at the time. Contrary to this love being a

commonplace occurrence, David loved Jonathan ‘as he loved his own soul’ – a

phrase having ‘no parallel anywhere else in the Jewish Scriptures’ (Boswell

1994).

In biblical times it became the archetype for true, lasting love,

pointedly set against the transitoriness of heterosexual passion.

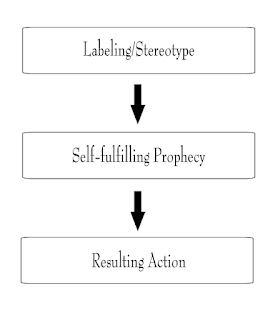

The relationship between language and experience has been one of

the central problems of philosophy for centuries. In more recent times the

issue has been the complex relationship between language and identity. The

social constructionist school maintains the omnipotence of words: I label you,

therefore you are. The school is rooted in structuralism, a linguistic/semantic

approach to literature, in which text rather than context is the final arbiter

of meaning. The sociological development of the theory maintains that the

homosexual did not exist as a personality type or identity until he (or she)

was labelled, that the labelling occurred in the work of the sexologists in the

late nineteenth century, and that therefore homosexuals did not exist until

they were created, i.e. constructed, in the late nineteenth century.

The

traditionalist or essentialist rejects the philosophical presumption that

meaning precedes experience, and adopts the common-sense view that homosexual

identity precedes labelling. Despite the sophistication with which social

constructionists deal with epistemes and semiotext(e)s, they are profoundly ignorant

of historical linguistics.

In the search for specific words or labels for homosexuality we

should not ignore the fact that most people use euphemisms or phrases made up

of ordinary words to describe what they do. Even today most people do not use a

specific word to describe themselves when engaged in intercrural intercourse,

although slang words are available. When General Kuno Count von Moltke

explained in court his sexual relations with Philipp Prince zu

Eulenburg-Hertefeld, in the first decade of the twentieth century, all he could

say was this: ‘Fooling around. I don’t know of no real name for it.

When we

went rowing we just did it in the boat.’ ‘Fooling around’ was perhaps the most

frequently used euphemism during the 1920s through 1940s, and is probably still

the term used by adolescents engaging in their first ‘experiments’. In the

early 1930s British gay men referred to each other as ‘so’ and ‘musical’, terms

gradually supplanted by ‘queer’, which may have been used earlier by the Irish

and was popularized in theatrical circles (Skinner 1978). To say that such

words show lack of scientific refinement is quite true, but everyone knows

exactly what they mean – even when they use such vague terms as ‘it’ and ‘that

way’.

The absence of language does not indicate the absence of

conceptual thought. The concept of lesbian sex existed even when no particular

term was used to identify it. Donoghue (1993) documents the use of generic

terms such as ‘kind’, ‘species’ and ‘genius’ (i.e. genus) in mid-eighteenth-century

discussions of lesbians, abstract phrases such as ‘feminine congression’ or

‘accompanying with other women’, and abundant euphemisms: ‘irregular’,

‘uncommon’, ‘unaccountable’ and ‘unnatural’, ‘vicious Irregularities’,

‘unaccountable intimacies’, ‘uncommon and preternatural Lust’, ‘unnatural

Appetities in both Sexes’, ‘unnatural affections’, ‘abominable and unnatural

pollutions’.

There is much evidence to suggest that the earlier use of the word

‘hermaphrodite’ was as much a euphemism for ‘homosexual’ as the modern term

‘bisexual’. There is ever-increasing pressure towards abstraction; in many

circles today, gay men are called ‘men-who-have-sex-with-men (MSM)’, while

lesbians are regularly called ‘women-loving-women’. On the Internet, all groups

are now embraced within the acronym MOTSS (members of the same sex) or LGBTQ

(lesbian gay bisexual transgender queer). This may be convenient, but I don’t

think it is an advance in epistemology.

We do have to acknowledge that there do not seem to exist words in

early languages which correspond to male and female homosexual, or male and female same-sex relations

simultaneously. In other words, there don’t seem to be any words for this high

level of abstration until the discipline of sexology begins in relatively

modern times.

It does not necesssarily follow, however, that there were no

words for homosexuality as a general concept, and that it was not until the

modern age that abstract, generic, ‘scientific’ terms were invented for

homosexuality. Before we attach too much significance to the absence of terms

that simultaneously cover male and female homosexuality, consider the

following.

When modern people use the word ‘homosexual’ or ‘homosexuality’,

nine times out of ten they are thinking of male same-sex relations. Only at the last

minute will they say, ‘Oh, yeah, this includes women too’, but even then they

will probably use the other term ‘lesbian’. When the terms were coined in the

late nineteenth century, they were used predominantly – in fact almost entirely

– in the context of legal prohibitions against sex between men. ‘Inverts’ were

almost always considered to be men.

When John Addington Symonds worked with

Havelock Ellis on the bookSexual

Inversion, the first book on homosexuality in English, only at the

last minute was Symonds persuaded to include a chapter on female homosexulity

in his historical survey. (Ellis’s wife Edith was a lesbian, and she got her

lesbian friends to contribute their case studies to the project. In her circle,

they used the word ‘lesbian’ rather than ‘female sexual

inversion/homosexuality’, but eventually this was sublimated into the abstract

consideration by her husband.)

A second thing to consider is that it is really only in the

English language that you can have one single word for both sexes, because

European (and most other) languages require different forms for masculine and

feminine (and neuter) nouns etc. Strictly speaking, the words that were coined

in German were homosexualist (which means ‘male homosexual’) and homosexualistin (which means ‘female homosexual’).

The

same division is true for other equivalent words (e.g. in Ulrichs’s system Urningthum meant specifically male homosexuality,

the Urningwas specifically a male homosexual, and

the female homosexual was anUrningin.

Ulrichs’s classification system has more than 30 terms, but though they are all

very ‘scientific’ and abstract, the only term that applies equally to men and

women is Urnische Liebe,

‘homosexual love’ (though even that is really used most of the time about men).

When we stand back and look at his system, it appears as though he has

conceptualized the abstract concepts of ‘the homosexual’ and ‘the bisexual’ and

‘the heterosexual’, but I think all his concepts, strictly speaking, label

specifically male or female examples of these.

The claim that in ancient and indigenous cultures there are no

words for homosexuality as a general concept, is true only if you insist that

the term simultaneously encompasses men and women. Even then it’s not entirely

true, because Aquinas defined ‘the vice of sodomy’ as ‘male with male and

female with female’, which satisfies the requirements for abstract

inclusiveness. If you don’t insist that the term encompass men and women, then

you will find terms for male homosexuality and male homosexuals as general

concepts, and female homosexuality and female homosexuals as general concepts,

and male and female heterosexuals and heterosexuality as general concepts.

For example, ancient cuneiform texts have been found describing

male homosexuality as a generalized concept, ‘the love of a man for a man’, and

one cuneiform text mentions lesbians. As early as the third century BC Hellenic

writers coined the word gunaikerastria to denote sexual relations between

women. This term means ‘female lover of women’ and is as scientific a term as

one could wish, less euphemistic than ‘lesbian’, more economical than ‘sex

between women’, and devoid of value judgements.

There were many ancient terms for abstract concepts or categories

of homosexual. In the Byzantine Empire there were several words for male

homosexuality in general (rather than words for effeminate or receptive

homosexuality in particular): paiderastia,

pederasty; arrhenomixia,

mingling with males; arrhenokoitia,

coitus with males. The two latter terms are perfect behaviourist equivalents to

‘homosexuality’.

Paiderastia, from Classical Greek paiderastes, boy-lover, is

itself a general concept, strictly speaking no narrower than the modern

‘man-lover’. Boswell (1994) points out that ‘the most common words for

"child" in both Greek (pais) and Latin (puer) also mean

"slave," so in many cases when an adult is said to be having sex with

someone designated by these terms it could simply be with his slave or

servant’.

In other words paiderastia, pederasty, is not necessarily

narrowly confined to boys, but may be closer to ‘homosexuality’ than modern

historians acknowledge. The pederastic pair consists of the erastes and the eromenos, ‘lover’ and

‘beloved’; we can infer an active/passive division, but strictly speaking these

are not examples of inserter/receptor terminology, and the term ‘boyfriend’ was

not used in a particularly derogatory fashion. The modern Greeks, under the

influence of (American) English usage, have abandoned these terms, and use the

awkward term omophylophilia.

Metaphors and tropes are as important for understanding homosexual

culture as more precise ‘scientific’ terms. Among the ancient Toltecs

(conquered by the Aztecs), queers worshipped the transgender god/goddess of

non-procreative sexuality and flowers named Xochiquetzal, and sodomy was called

the ‘Dance of the Flowers’.

In China, metaphors such as ‘the passion of the cut

sleeve’ or ‘the southern custom’ encompassed queer-cultural values of love and

loyalty for some two thousand years. The earliest Chinese word referring to

homosexual relations dates from the sixth century, nanfeng, literally ‘male wind’

(still used today as a literary expression for male homosexuality), perhaps

more accurately translated as ‘male custom’ or ‘male practice’ (Hinsch 1990).

Another term from this period is nanse,

male lust or male eroticism (se denotes

sexual attraction or passion). These words are as abstract (hence ‘scientific’)

as the word ‘homosexuality’ coined thirteen hundred years later.

Nanfeng actually has two sets of characters

pronounced the same, one meaning ‘male custom’ and the other meaning ‘southern

custom’ (‘man’ and ‘south’ are both pronounced nan). Homosexuality is believed

to have been especially popular in Fujian and Guangdong, the southern regions

of China, and ‘southern custom’ was the term for homosexuality during the Ming

period; nanfeng shu, the

southern custom tree, which consists of two trees, one larger than the other,

entwined with one another to become one, was a standard icon of homosexuality

in Chinese literature (Ng 1989, Hinsch 1990).

The Chinese language is particularly rich in queer metaphors that

do not relate directly to sex/gender roles, but to a larger complex of queer

culture with an emphasis upon desires, tendencies, preferences and emotional

commitments rather than sexual acts.

Apart from Chinese, Tamil and Kannada language is rich with queer metaphors according to Keshiraja's Sapthamanitharpana (Kannada Grammar) he refers more than 9 genders. Tamil texts and Grammar supports gender diversity.

The two main terms for male homosexual

relations, ‘passion of the cut sleeve’ (duanxiu pi orpian) and ‘joy of the shared

peach’ both derive from ancient stories about specific emperors and their

favourites dating back to the sixth century BC, a literary tradition kept alive

for more than two thousand years. ‘Emperor Ai [reigned 6 BC—1 AD] was sleeping

in the daytime with Dong Xian stretched out across his sleeve. When the emperor

wanted to get up, Dong Xian was still asleep. Because he did not want to

disturb him, the emperor cut off his own sleeve and got up.’ This story ‘was

alluded to repeatedly in later literature and gave men of subsequent ages a

means for situating their own desires within an ancient tradition. By seeing

their feelings as passions of the "cut sleeve," they gained a

consciousness of the place of male love in the history of their society’

(Hinsch 1990).

The story of the fickle emperor Duke Ling of Wei (534–493 BC) and

his devoted favourite Mizi Xia was so famous that his very name became a

catchword for homosexuality, and ‘the joy of the half-eaten peach’ became one

of the most frequently used phrases to denote homosexuality in general for more

than two thousand years. ‘Another day Mizi Xia was strolling with the ruler in

an orchard and, biting into a peach and finding it sweet, he stopped eating and

gave the remaining half to the ruler to enjoy. "How sincere is your love

for me!" exclaimed the ruler. "You forgot your own appetite and think

only of giving me good things to eat!"’ (Hinsch 1990).

However, later when

the ruler’s ardour cooled, Mizi Xia was executed for committing some crime

against Duke Ling, who professed not to believe his innocence. ‘"After

all", said the ruler, "he once stole my carriage, and another time he

gave me a half-eaten peach to eat!"’ This is obviously a poetic symbol,

and it seems to me that like all symbols it encapsulates an essence, in this

case the essence of homosexual love. It is also worth noting that the metonym

of the half-eaten peach connotes a generalized eroticism rather than any

specifically active or receptive sexual role, emphasizing the mutual sharing of

the fruits of that love.

The male prostitutes who flourished in late Imperial China were

calledxiaochang, little singers. By the time laws were promulgated to

regulate homosexuality during the Ming dynasty, the legal term for

homosexuality was jijian,

a derogatory term meaning ‘chicken lewdness’, from ji, chicken, and jian, ‘private, secret’, which

may reflect a popular belief about the behaviour of domesticated fowl.

By 1985,

in Taiwan, a long and noble history of poetic metaphors had been replaced by an

exact translation of the most notorious Western euphemism: Bugan shuo chu kou de ai – ‘The love that dare not speak its

name’!

No comments:

Post a Comment